Alex Jones was in the news recently for his absurdist trial, and a tweet I stumbled upon gets at something I find particularly interesting about conspiracy theories:

This tweet summarizes the only theory I actually subscribe to: a meta-conspiracy in which reality is in fact far more sinister and manipulative than the fantasy scenarios dreamt up by conspiracy theorists. The truth tends to be as upsetting or worse than the parallel false stories invented by Jones and his like – but we rarely characterize it as such.

Here, I will describe four world real conspiracy theories, plots hatched behind closed doors by business executives and politicians. With these stories, ask yourself – are they really any more outlandish than a faking of the moon landing? Any less nefarious than a Kennedy assassination plot?

And it will be on one of my favorite subjects: the auto industry.

Lead in the Gasoline: How One Guy Killed Millions

It shocked me, recently, to learn just how we ended up with the “unleaded” label at gas stations. I’ve of course always seen that label since high school, when I had to start buying gas. Though one could obviously deduce that there must be such a thing as “leaded” gas, I could’ve hardly imagined the explanation for why lead was ever in gasoline in the first place, nor the dark story of its promotion and subsequent impact on society – a truly evil conspiracy.

Early in the history of the automobile, gasoline did not interact perfectly with the engine; there was a “knocking” problem involving imprecise explosions in the combustion chamber. The full story is is beyond the scope of this article, but, in short, one man discovered a solution in the 1920s: chemical engineer Thomas Midgley Junior.

This dude was bad news.

Midgley had been experimenting with different additives to gasoline, trying to identify that which would most effectively eliminate the knocking effect. In fact, ethanol turns out to be the most effective at fixing the problem, but for profitability he identified tetraethyl lead (TEL). His boss at General Motors, Charles Kettering, was thrilled that such a valuable additive had been discovered, but unfortunately lead has the nasty feature of being a highly toxic substance.

Undeterred, GM aggressively marketed the additive as a superior gasoline, advertising its performance and knowingly downplaying the poisonous side effects. Both Midgley and Kettering were well aware of how dangerous lead was – in fact, Midgley himself repeatedly experienced severe lead poisoning and received warnings from other scientists about it being a “a creeping and malicious poison“. During the manufacturing process, many employees of GM (and partner company Du Pont) died from its effects.

Despite all this, the company insisted that TEL was in fact safe – but they required that advertising not include the word “lead” in the text. In an especially audacious instance, Midgley confronted workers outraged about conditions involving lead at a GM facility press conference, and to demonstrate its safety rubbed TEL all over his hands. He had been on a beach recovering from lead poisoning in the weeks prior.

Of course, this was in the heyday of GM and the product was wildly successful. From its invention in the 1920s until the mid-1970s, leaded gasoline spread around the world and GM reaped the benefits of their ingenuity. However, research was catching up and by the 1980s the dangers of leaded gasoline had been established; we have since learned that it kills, reduces IQ, and might even contribute to crime waves. TEV had become an internationally dominant product, but from around 1995 to 2005 was phased out and banned across the world.

It is hard to say how many died from this product, but estimates are in the millions per year. Lead remains in the soil across the world, poisoning children from California to London. Midgley went on to invent Freon, which briefly obliterated the ozone layer. Real cool guy, this Midgley fellow.

There isn’t really a happy ending to this story (unless you’re a GM shareholder from the 1930s, I guess), but needless to say it was an active effort from a corporation to spread poison across the planet for profit – and might only be remembered today if you take note of the “unleaded” label at your gas station.

Segregation by Design: Racist Bridges and Urban Renewal

In the past five or six years, there has been some reporting about the cruel and racist practice of “redlining” in the real estate industry. In short, the idea was to sell nice neighborhoods to white families and bad neighborhoods to black families.

This on its own is of course a horrendous conspiracy, extending across the nation and in support of a segregated system, but this article is on the subject of automobile conspiracies. So how does that tie in here?

To put it bluntly, entire neighborhoods were demolished for highways, typically black neighborhoods, and often successful ones:

This of course did a phenomenal job of dividing communities, which works hand-in-hand with the redlining practice. To this day, cities across the country are living with the consequences of these projects. With highway construction came an abundance of parking lots, and once-thriving areas in major American cities were razed to the ground. Not through bombs, as with Europe and Japan in World War Two – but by our own leaders in government under the guise of “urban renewal”.

Of course, the decision to build these highways was just that – a decision. Were the people in charge really this racist? Did they intentionally build this infrastructure in such a destructive manner?

One such leader was Robert Moses, the “power broker“, who implemented the highway system in New York City and influenced city planners nationwide. As it turns out, yes, Robert Moses was insanely racist and absolutely did design his highway system in a way that led to suburban sprawl, car dependence, intensified segregation, and frequent demolition of thriving parts of New York City.

He was the most racist human being I had ever really encountered. The quote is somewhere in there, but he says, “They expect me to build playgrounds for that scum floating up from Puerto Rico.” I couldn’t believe it. –Robert Caro on Moses

The example which most typifies this attitude is his notorious (purported) approach to bridges. According to the authoritative biography on Moses by Robert Caro, he intentionally built bridges on the route to Long Island beach towns at such a low level that buses could not pass underneath them – presumably, buses serving the poorer minority communities of New York. In other words, he discouraged anyone who could not drive in a car from visiting the beach.

The veracity of this specific allegation is debatable, but one thing is not – that Moses intentionally pursued a car-centric policy as city planner, and all the infrastructure he developed. As Caro writes:

Moses was a real genius … He engineered the footings of the LIE to be too light for anything but cars, so you can’t ever put a light rail there. He condemned Long Island to be this car-centered place.

No matter what the specific project is, it seems that “urban renewal” and the work of Robert Moses had at its core a car-centric vision of the world, one which came at the expense of the communities which were most vulnerable. Moses himself put it best:

I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without moving people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs

The Invention of Jay Walking

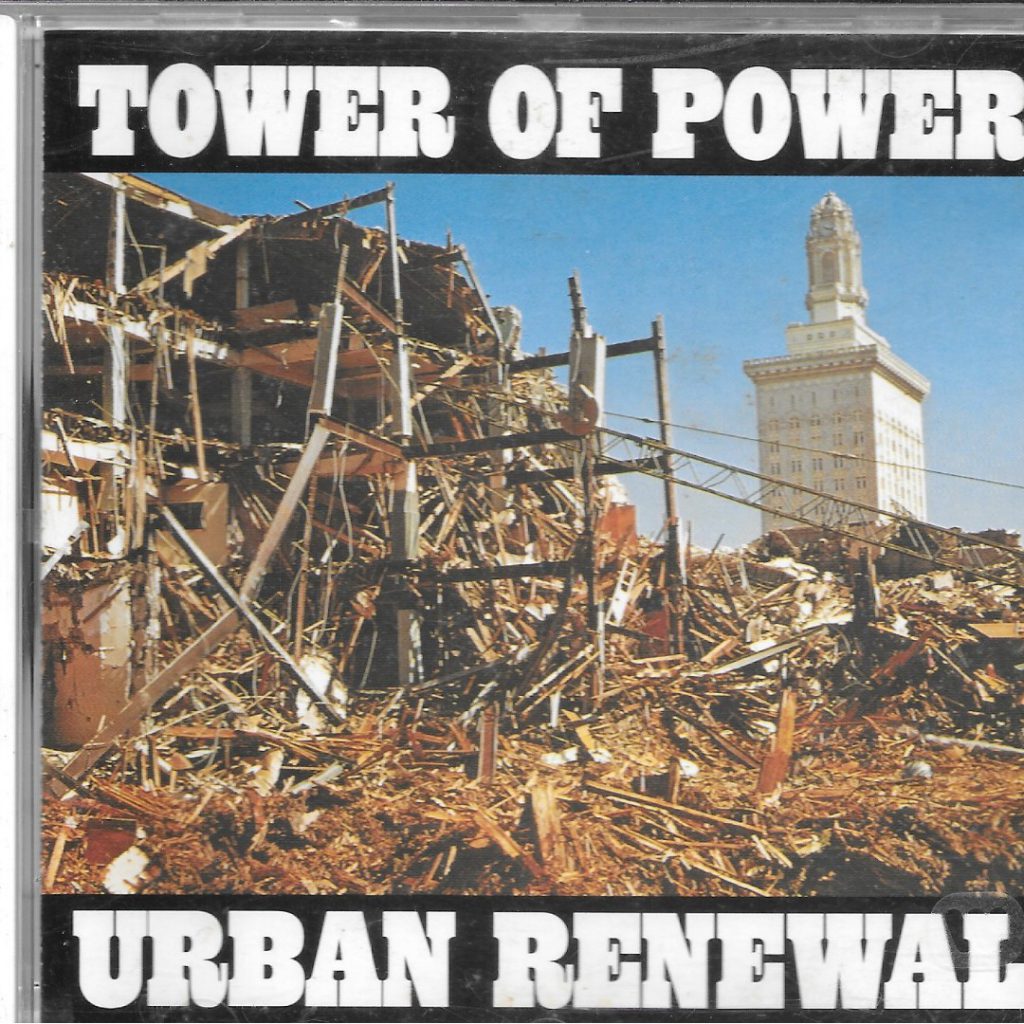

Marketing from the auto industry is often the most insidious tool, used to enforce a subtle shift in thinking in the masses. Nowadays it’s easy to imagine the sort of advertisements the companies use to sell pickup trucks for $50K. But in this example, they go the extra mile and a completely new crime is invented simply to alienate people who aren’t driving.

We all know what jaywalking is: it’s when a pedestrian crosses the street without having permission to do so. However, this is a very new concept in the grand scheme of history. If you look at photos from a hundred years ago, often you will see scenes of folks crossing the street whenever they want, sharing the road at will with stage coaches, bicycles, street vendors, and other pedestrians.

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2936360/82104296.0.jpg)

However, automobiles are fast. And heavy. And, most importantly, dangerous. So when the city of Cincinnati nearly forced cars to mechanically limit their speed to 25MPH in 1923 (itself another entire discussion) the car companies realized they could face resistance from the population and mobilized to portray the pedestrian as the one responsible for safety.

There were no laws on the books at the time governing how a pedestrian could cross a street, but the auto industry sought to change that. The term “jay” basically meant “country bumpkin”. By basically calling people idiots if they crossed the street on their own, responsibility was successfully shifted from car drivers to pedestrians, and the idea of jaywalking was invented through aggressive marketing. As historian Peter Norton notes, “The newspaper coverage quite suddenly changes, so that in 1923 they’re all blaming the drivers, and by late 1924 they’re all blaming jaywalking”.

From there, with the psychology successfully established, it was simply a matter of turning the offense into an official crime. Local municipalities took up this effort with gusto, and by the 1930s it was a cultural norm. Today it feels as if police are more likely to enforce jaywalking rules than speeding. As one author notes, this is a common tactic by corporations – to shift responsibility onto the consumer, such as with recycling practices, for example – so perhaps the prevalence of this sort of conspiracy would come as a surprise to many.

Death of the American Trolly

If you go far enough back in time, Los Angeles had a functioning public transit system in the form of a streetcar/trolly network. Sadly, it is no more. The demise of this transit system is particularly interesting in the context of conspiracy, as there is a spurious myth of why it collapsed and the mundane, true story.

The exciting, more nefarious story even I myself was convinced of was that the car companies formed a cartel and bought up the streetcars, decommissioning them as a way to instigate more car purchases. It’s even a plot in that strange cartoon movie from my childhood Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Based on the previous stories described in this article, this story seems perfectly plausible – these companies really will engage in insanely unethical business practices. However, the truth here is a bit more nuanced, and in a way even more upsetting when you consider the implications.

In brief, the privately operated trolly systems were out-competed by cars and, in a way, by buses. The important detail in this story is that streetcars needed to use public roads to get around, and therefore would end up sharing the street with increasingly popular automobiles; congestion meant that the travel times on the streetcar routes increased substantially, making it more appealing to buy one’s own car, therefore increasing congestion, etc. – a vicious cycle. Additionally, the streetcar companies were on the hook to maintain the roads they utilized, so they ended up subsidizing infrastructure for their competition, the automobile.

So technically there isn’t a grand conspiracy from the car companies to destroy public transit – but the reality isn’t far off. Market mechanics that a libertarian would adore resulted in less choice available in cities like Los Angeles; owning a car in that city is not an option, it’s a precondition, an offer you can’t refuse. And consider the fact that congestion – the reason streetcars vanished – can be priced correctly, or that dedicated lanes can improve bus/trolley performance. These are necessary considerations in the overall transportation system, but instead we experience what is effectively a monopoly.

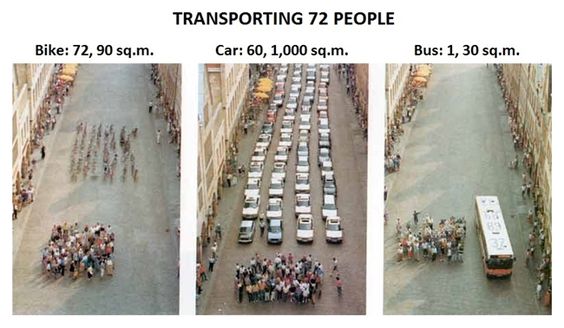

The fact of the matter is that by the 1950s cars had won. Public transit was poor and degrading, apparently, and America was a culture of the automobile. The banality of no alternative option is the conspiracy, where even walking can be a crime. Bicycles aren’t allowed on the sidewalk, and are hated in the street. Across the nation and the world, corporations subjugated walking, streetcars, and bicycling to second class status. That’s the real conspiracy here.